This Ultimate Guide to Matcha was written in collaboration with Katrina Wild, tea expert, traveller and writer.

Before you read our Ultimate Guide to Matcha, we wonder how much do you already know? This powdered Japanese green tea has been a hot-growing trend for quite a while now not only because of its fantastic taste, but because of Matcha’s ability to help you focus, the health benefits that come with ingesting powdered tea leaves packed with antioxidants, its fascinating cultural history and, really, its captivating, compelling colour.

We get asked so many questions about it. There’s just so much to know. We decided it was about time we wrote the longest, most comprehensive guide to Matcha tea, answering every thought about Matcha you ever had. Are you ready? Have you made yourself a Matcha? Let’s go!

If you’d prefer to jump to certain sections, here’s the index:

Understanding different Matcha cultivars

Matcha accessories and preparation

What is better? Organic or Non Organic Matcha?

What Is Matcha?

Matcha (抹茶), a Japanese green tea, is crafted from tender ‘tencha’ tea leaves harvested during the early spring and autumn seasons. These leaves undergo meticulous grading and auctioning, with the finest batches commanding top prices due to their exceptional quality and unique attributes resulting from careful farming techniques. Following purchase, the leaves are steamed, dried, and finely ground into a powder, typically using stone mills to achieve the desired texture. This powdered green tea, known as Matcha, holds a special place in Japanese culture, being central to the traditional tea ceremony, or chado, where its preparation symbolises meditation and silent communication.

Beyond ceremonial use, Matcha has gained popularity in modern cuisine, featuring prominently in chocolates, confectioneries, baked goods, and latte-style beverages. Culinary-grade Matcha, preferred for these applications, often carries more pronounced robust notes, ensuring its distinct flavour shines through amidst other ingredients.

We have exclusively designed our Matcha Ceremonial Grade Kagoshima Natural Farming with the ristretto base for flat white coffee in mind, which balances sweetness and strength. Our blend of ceremonial first harvest Yabukita, Okumidori, Okuyutaka and Zairai cultivars allow the rich, authentic taste of Matcha to shine through milk or milk alternatives, or as a premium culinary ingredient in cocktails, speciality beverages, desserts, and food. We refer to it as the ‘creme de la creme’ of ingredients, akin to a really good extra virgin olive oil (more to come on this later).

A Brief History of Matcha

Matcha has a history that traces back to China during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), where the practice of grinding tea leaves into a fine powder and whisking diancha (點茶; whisking powdered tea) first emerged. However, it was in Japan where Matcha truly flourished and became an integral part of Japanese culture. Thanks to a Japanese monk named Eisai (明菴栄西, 1141 – 1215) the arrival of Zen Buddhism in Japan in the 12th century brought with it tea, which later evolved into tea ceremony around the 15th century, or chanoyu, which emphasised mindfulness, simplicity, and the appreciation of beauty. Matcha became central to this ceremony, prized for its vibrant green colour, deep flavour, and the sense of calm it imparted to those who consumed it.

Over the centuries, Matcha production techniques evolved, with innovations such as shading the tea plants to enhance chlorophyll production and steaming the leaves before drying and grinding them into powder. Today, Matcha continues to be celebrated not only for its cultural significance but also for its health benefits and unique flavour profile.

Japanese Matcha Ceremony

The Japanese tea ceremony, known as Chanoyu (茶の湯 – hot water of/for tea) or Sadō/Chadō (茶道 – the way of tea), holds profound cultural and spiritual significance, blending artistic expression, Zen philosophy, and social etiquette. Stemming from the concept of suki (数奇; aesthetics), chanoyu encompasses various facets, including Zen meditation, performance art, and hospitality.

Historically rooted in the 12th century with figures like Eisai and evolving through Murata Jūko and Sen-no-Rikyū, chanoyu embodies principles of simplicity, harmony, and mindfulness. Practised within purpose-built tearooms ( 茶室; chashitsu), the ceremony unfolds through the intricate temae (点前) tea preparation process, emphasising purification rituals, harmonious utensil arrangement, and the serving of tea with utmost respect and tranquillity.

Guests engage in haiken (拝見 – viewing/appreciation), deepening their understanding of chanoyu’s aesthetic and philosophical underpinnings. Expressions like ” Tea and Zen are one taste” (cha zen ichimi; 茶禅一味 -) and “One lifetime, one meeting” (ichi-go ichi-e; 一期一会) underscore the interconnectedness of Zen Buddhism and chanoyu, as well as the impermanence and uniqueness of each moment.

There are various schools or styles (ryūha; 流派) of chanoyu differing in tea preparation and philosophies as well as by context, i.e., practised by samurai or merchant class, the most well-known schools being Urasenke (裏千家), Omotesenke (表千家), Mushakōjisenke (武者小路千家). With its rich history, intricate practices, and timeless wisdom, the Japanese tea ceremony continues to captivate and inspire practitioners and enthusiasts alike, embodying the essence of Japanese cultural heritage.

Japanese Matcha Terroirs

The concept of terroir, familiar to wine enthusiasts, also applies to Matcha production in Japan, with distinct flavour profiles shaped by microclimates, varietals, and production methods. Uji, the birthplace of Matcha in Kyoto Prefecture, offers low-temperature processing yielding floral, umami-rich, and creamy notes coveted in high-grade ceremonial Matcha.

In contrast, Fukuoka’s warmer climate results in buttery and nutty flavours, with Yame highly recognized for its loose-leaf teas such as Gyokuro (玉露) and Sencha (煎茶).

Shizuoka, Japan’s largest tea-producing prefecture, also focuses more on loose-leaf green tea but produces some Matcha with expected umami and sweet notes. Kagoshima’s volcanic soil nurtures vegetal, bitter, and umami-rich Matcha, while Nishio in Aichi Prefecture delivers sought-after, high-quality Matcha with a balance of sweetness and umami. Despite regional variations, factors such as processing techniques and final preparation also influence Matcha’s flavour profile, emphasising the complexity of this revered Japanese beverage.

What does Matcha taste like?

The taste of Matcha is a harmonious blend of sweet, umami, astringent, and vegetal flavours, resulting in a unique and complex profile. The sweetness, akin to fresh green vegetables or grass, balances the slight bitterness, contributing to a well-rounded taste experience. The umami, often described as savoury or brothy, adds depth and richness to the flavour profile, while the vegetal notes evoke images of lush greenery.

The overall taste of Matcha can vary depending on factors such as the quality of the tea leaves, the growing conditions, terroir, harvesting and processing techniques employed, storage, and the preparation method, making it an intriguing and delightful beverage to explore.

Matcha Production

Cultivation

Cultivation is the foundation of Matcha production, where the choice of cultivar significantly impacts the final flavour. Various cultivars are popular for Matcha, often blended to achieve a balanced taste profile. While some brands market their teas as ‘single origin’ or ‘single cultivar,’ taste superiority isn’t assured, as quality depends on factors like farming expertise, steaming techniques, and milling methods. Selecting the right tea plant, akin to choosing a grape variety for wine, is crucial.

As you may already know, all tea originates from the Camellia Sinensis plant, which has two primary varieties: var. assamica and var. sinensis. Within these varieties are plants with unique traits, known as cultivated varieties or cultivars. Cultivars are groups of plants bred to possess specific desirable characteristics, sharing identical genetic compositions inherited from their mother plant. Japan boasts approximately 150 cultivars, both officially registered and unregistered, comparable to grape varieties in wine like Merlot and Primitivo or coffee like Blue Mountain and Geisha.

Cultivars can be tailored to various weather conditions or flavour profiles, as well as for types of cultivation such as sencha for open field cultivation or matcha for shaded growth. While Yabukita is the most widely used cultivar, comprising 70-80% of Japan’s tea production, it may not be the ideal choice for Matcha. Many shaded tea cultivars originate from Uji, Kyoto, the primary region for gyokuro and Matcha production, as well as shaded sencha (kabusecha; かぶせ茶). Well-known examples include Asahi, Gokou, Ujihikari, Samidori, and Ujimidori among many others, frequently encountered when seeking Matcha.

Shading

In the dormant winter months, the tea bush halts its growth to withstand the cold weather, absorbing nutrients from the soil into its roots. This nutrient accumulation fortifies the plant, preparing it to survive the frost until the arrival of spring. As the temperature rises and spring beckons, the tea bush emerges from its hibernation, gradually transferring the stored nutrients to the newly sprouting buds, which are destined to yield Japan’s most exquisite tea.

Shading the tea leaves for 4-5 weeks prior to the first spring harvest is a critical practice in Matcha production. By reducing sunlight exposure upto 85%, the tea plant produces more L-theanine, enhancing the tea’s umami flavour and sweetness while diminishing the presence of catechins responsible for bitterness. Additionally, the shading process imparts a distinct aroma reminiscent of green seaweed referred to as covering aroma (被覆香り; hifuku kaori; 覆い香り; ooi kaori), attributed to the presence of dimethyl sulfide. Moreover, the heightened chlorophyll production stimulated by shading contributes to the lush green coloration of the tea leaves, a visual hallmark of high-quality Matcha.

To achieve this, farmers employ various shading methods (被覆栽培; hifuku saibai) , each with its own nuances. Traditional approaches, such as the traditional honzu technique (本簾被覆; honzu hifuku), involve using straw to provide partial shade, allowing for gradual adjustment based on weather conditions but demanding labor-intensive efforts.

In contrast, modern methods utilise black synthetic fiber (寒冷紗; kanreisha), offering precise control over shade intensity and uniformity. This synthetic material is often employed in tunnel shading (トンネル被覆; tonneru hifuku), dual-layered shading (棚型二段被覆; tanagata nidan hifuku), or direct shading methods (直接被覆; chokusetsu hifuku), each tailored to specific tea types and production goals. Beyond aesthetic considerations, shaded cultivation profoundly impacts the flavour and aroma of the tea.

Harvest

Matcha harvesting, typically occurring in late spring when leaf production peaks, plays a pivotal role in determining Matcha quality. Traditional handpicking ensures only the top two leaves and a bud, suitable for high-quality Matcha, are selected. However, due to rising labour costs, mechanised harvesting methods are increasingly used, although they pose challenges to traditional practices and require different tea farm composition. Despite the efficiency of machines, handpicking remains integral for ensuring Matcha of the highest calibre. Leaves harvested in summer or autumn are typically used for lower-grade Matcha products, such as lattes or culinary applications.

Processing Tencha

After harvesting, tea leaves undergo immediate processing, including steaming and drying in specialised tencha ovens ( 碾茶炉; tencharo). Unlike most Japanese green teas, Matcha leaves are not rolled, resulting in distinct flaky tencha leaves. The initial steaming process, lasting approximately 20 seconds, deactivates oxygen in the leaf to maintain its green colour and freshness while eliminating undesirable odours.

Following steaming, the leaf is propelled by wind turbines in 4-5 columns, allowing for moisture evaporation and cooling, as well as the air helps the leaves that are stuck together to detach. The leaf is then conveyed through an approximately 10-metre long brick oven with three or four layers of conveyor belts for even and gradual drying, a process critical for ensuring uniformity and preventing burning. Invented in 1924 by Horii Chōjirō (堀井長次郎), the tencha oven machine revolutionised drying, replacing hand processing and enhancing tea quality.

The dried leaves, known as ‘raw tencha’ (荒碾茶; ara-tencha), undergo further refining, removing stems and veins, including cutting into uniform flakes ideal for grinding, filtering, and final drying, typically conducted at the wholesaler or tea vendor. In the traditional tea market, the purchasing method called ‘iritsuke’ (入着け) relies on strong farmer-vendor relations, while a more contemporary approach involves the ‘hinpyōkai’ (品評会), or tea auction, held exclusively in Kyoto since 1974.

At these auctions, buyers seek specific flavours, aromas, and colours conducive to their final blending objectives. Only after successful final processing and possible blending is the tea referred to as finalised tencha, ready for Matcha production. Unlike Matcha, which is rarely stored in powdered form due to oxidation risks, tencha is preserved in leaf form, allowing it to age and mature while maintaining freshness for longer periods. When needed, the tea is milled using a stone mortar before being shipped to vendors or customers, ensuring optimal quality, freshness, and flavour retention.

Grinding

The final step involves grinding tencha leaves into the fine powder known as Matcha. Traditional granite stone mill grinding, albeit slow, ensures high-quality Matcha. Commercial grinders may produce as little as 400 grams a day due to their slow processing speed (approximately 30-40 g per hour). To prevent powder degradation, factories grind Matcha in temperature and humidity-controlled environments. While other grinding methods are employed for higher volume and lower cost, like jet milling, they may sacrifice some quality compared to stone mill ground Matcha.

Matcha Preparation Tools

Matcha preparation tools, known as sadōgu (茶道具) or dōgu for short, are essential for preparing Matcha in the traditional Japanese tea ceremony. These utensils are not merely functional but are often regarded as exquisite works of art. During a tea gathering, the host carefully selects pieces that harmonise with each other, a practice known as toriawase (取り合 わせ), to create a cohesive theme or reflect the current season. When making Matcha at home, essential tools such as a bamboo whisk (chasen), a bamboo scoop (chashaku), a tea bowl (chawan), whisk holder (kusenaoshi), and a tea strainer (furui) are recommended for an authentic yet simple experience.

Chawan Bowl – 茶碗

The chawan is a simple ceramic bowl designed for both making and savouring Matcha. Originating in China and introduced to Japan in the 13th century, leading to a thriving artistic industry for their production. Typically short and wide in shape, chawan allows for easy whisking in an ‘M/W’ shape, creating a light foam on the surface of the Matcha. Historically, Chinese tea bowls like the Jian chawan, known as Tenmoku chawan in Japan, were favoured until the 16th century, with the term “tenmoku” derived from Tianmu Mountain in China. As tea culture spread in Japan, local adaptations emerged, such as the Seto-made copies of tenmoku during late Kamakura period (1185–1333), and the Korean-influenced Ido chawan during the late Muromachi period (1336–1573), prized for their simplicity during the wabi tea ceremony. Annan ware from Vietnam was also popular during the Edo period (1603 – 1868), reflecting diverse cultural influences and evolving ceramic craftsmanship. Today, esteemed chawan include raku ware, Hagi ware, and Karatsu ware.

Shop AVANTCHA Chawan Matcha Bowl

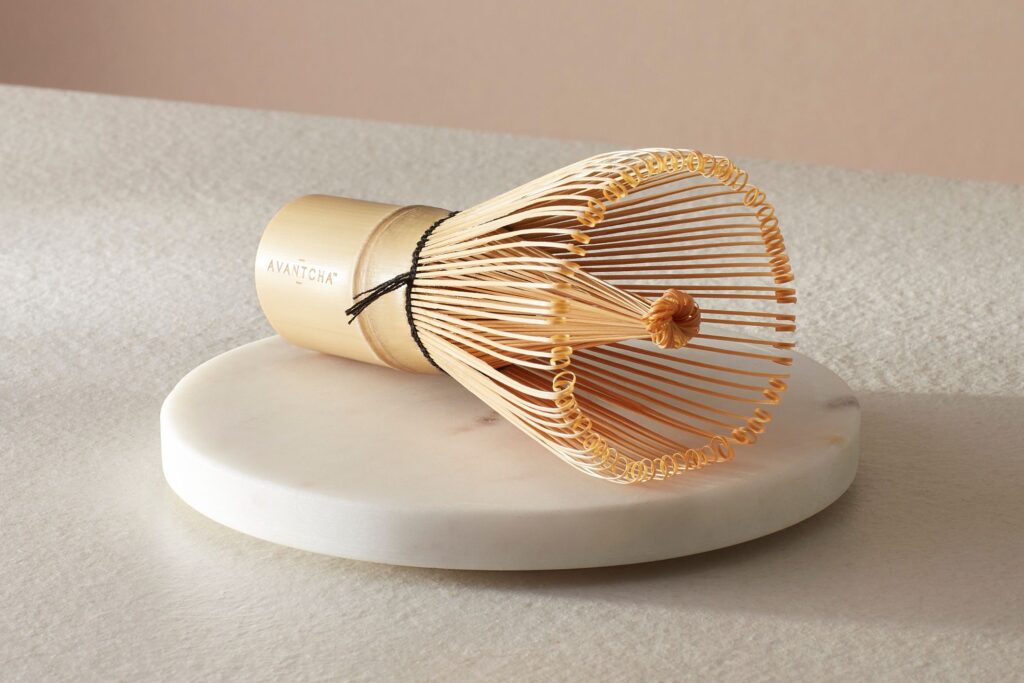

Chasen Whisk – 茶筅

The chasen, a traditional whisk for Matcha, has a storied history dating back over 600 years in Japan. Crafted from a single piece of bamboo with around 80-120 tines, seasoned for up to two years, the chasen is designed to coax Matcha into a light, even foam. Legend traces its origins to the 14th century, during the Muromachi period, when tea master Murata Jukō requested a high-quality whisk from Sosui Irido, a friend associated with Takayama Castle. This marked the inception of chasen craftsmanship, leading to the development of the delicate artistry seen in modern-day Matcha whisks. Today, despite the decline in traditional craftsmanship, a handful of master artisans in Takayama, Nara Prefecture, continue to handcraft chasen using locally sourced bamboo. The careful selection and sun-drying of bamboo contribute to its durability and quality, with each whisk exhibiting unique characteristics reflective of its maker’s expertise. While mass-produced alternatives exist, the timeless elegance and superior craftsmanship of Japanese-made chasen remain unmatched, embodying the essence of the Japanese tea ceremony.

Shop AVANTCHA Chasen Matcha Whisk

Chasen Kusenaoshi – くせ直し

To consistently make good Matcha, it’s important to take care of your chasen whisk by using a ‘kusenaoshi’ whisk holder to retain the curved shape and also safeguards its delicate bamboo tines from damage. Additionally, it serves as a convenient storage and display accessory for your chasen when not in use.

Shop AVANTCHA Chasen Kusenaoshi Matcha Whisk Holder

Chashaku – 茶杓

The chashaku, a slender bamboo scoop, serves the purpose of transferring Matcha tea powder from storage containers into the Matcha bowl with precision. Typically made of bamboo, the chashaku features a narrow and compact design, holding approximately half a teaspoon of Matcha powder.

Sieve – 篩

Upon opening freshly purchased Matcha, you might notice the formation of small clumps within the powder. These clumps occur naturally due to factors such as moisture and the weight of the powder settling over time. These clumps can slightly hinder the proper whisking of Matcha and can affect its smooth taste. A small sieve is specifically crafted to address this issue by conveniently sifting Matcha powder and breaking up clumps effectively. Designed in a compact size for convenience, it can be used to sift Matcha beforehand for tea ceremonies or at home.

Top Tip: When we were visiting our tea farmers in Shizuoka, however, their recommendation was to add the Matcha to the bowl with a little cold water and to mix this to a smooth paste before topping up with 70 degree water and whisking to a foam. They explained how using cold water in this way would remove any soft clumps, and also illicit the sweet ‘amami’ that Matcha naturally has, as well an ensuring that the ‘umami’ (savoury) notes could shine through. Why not try it both ways and see which you prefer?

How To Make Matcha

There are numerous ways to prepare and enjoy Matcha, catering to individual preferences and creativity. You can have a bit of fun experimenting and exploring here. Traditionalists relish the deliberate and slow process of making Matcha in a chawan bowl with a bamboo whisk, savouring each moment. However, for those seeking a quick health boost, an electric whisk or incorporation into smoothies works wonders. Matcha can even be shaken on-the-go or mixed with ice and milk in a cocktail shaker for a refreshing twist. For a pure Matcha experience, opt for high-grade varieties known for their rich and sweet flavour. When using Matcha as an ingredient, such as in cocktails, select a cocktail-grade Matcha – like our Matcha Ceremonial Grade Kagoshima Natural Farming.

If you choose to prepare Matcha traditionally, using essential utensils like a tea bowl, whisk, bamboo teaspoon, and sieve, here are simple instructions:

- Heat the tea bowl and bamboo whisk with hot water, then discard the water and carefully wipe the bowl. This step will also help you preserve your bamboo whisk.

- Sift the desired amount of Matcha into the bowl using a fine strainer with the aid of a chashaku spoon to prevent lumps and ensure a smoother foam. Approximately two chashaku scoops or one level teaspoon.

- Pour a small amount of cold water (10 ml) and softly mix the tea powder with water until an even paste without lumps.

- Pour hot water into the bowl (ideally 75°C to 85°C, however, in Japan, you might see boiling temperature used, which still makes wonderfully delicious Matcha with good foam; see what suits you the most) Whisk briskly making M/W shape at the surface of your drink. When the foam starts to form, raise the whisk carefully, making sure to burst any large bubbles.

- Enjoy your freshly prepared Matcha!

How to make Hot Matcha Latte >

How to make Iced Matcha Latte >

We are often asked if drinking Matcha is better than coffee. This really depends on personal preference and the way it has an effect on your unique body. If you’re looking to cut down on coffee, you could try the 30-day Matcha challenge and switch your daily coffee for Matcha and see how you feel, though we would argue that there’s room for both of these brilliant beverages within your day, in moderation. We have also been asked ‘…can I drink too much Matcha?’ (usually by customers who have discovered that they can’t get enough of it) and, again, we would suggest that you pay close attention to how you feel and take it from there.

If you’re sensitive to caffeine and find it has an impact on your sleep, the best time to drink Matcha would be in the morning. We would recommend enjoying any caffeinated beverages before midday and switching to herbal teas in the afternoon and evening. It’s good a thing we have plenty of herbal teas for you to explore…

Koicha and Usucha

Koicha (濃茶; thick tea) and Usucha (薄茶; thin tea) are two distinct types of Matcha enjoyed in the Japanese tea ceremony, each offering a unique experience in taste, texture, and cultural significance. Koicha, made from the highest grade tencha (碾茶) leaves, is characterised by its thick consistency, intense aroma, and rich umami flavour. It is meticulously prepared with a higher ratio of Matcha to water, typically using 4 g of Matcha and about 30 ml. The process of kneading the Matcha, known as matcha wo neru (抹茶をねる), requires skill and precision to achieve a smooth, syrup-like texture without producing bubbles. Koicha is often served in raku-yaki bowls, revered for their simplicity and association with the wabi aesthetic. It can be quite an intense umami and sweetness to it with a pleasant balance of bitterness and perfectly pairs with traditional Japanese wagashi sweets.

In contrast, usucha, or thin Matcha, is more commonly encountered outside the tearoom, with a lighter consistency and a focus on producing a layer of smooth foam through whisking (matcha wo tateru; 抹茶を点てる). This means that less tea and more water is used for the preparation. Usucha is enjoyed in seasonally appropriate decorative bowls, fostering conversations centred around the vessel’s design. Additionally, while each guest receives their own bowl of usucha, koicha is shared among participants, symbolising unity and shared experience.

If you wish to try making Koicha, we would recommend our Ceremonial Grade Yame for its sweet, creamy notes.

Organic Matcha Vs. Non Organic Matcha

Organic Matcha and non-organic Matcha offer distinct differences in farming practices and resulting taste profiles. Organic Matcha harkens back to traditional old Japanese farming methods when modern pesticides and fertilisers didn’t exist, reflecting a more grassy and earthy taste. In contrast, non-organic Matcha may undergo certain fertiliser use to achieve more abundant umami, balanced taste and more rich green hue.

If you’re drinking multiple cups a day, you might want to consider organic. It is common for many small tea farms to run by organic principles and yet not be classified as such owing to the cost and duration of accreditation. Organic Matcha has only become popular in the West in the last decade and so production is more limited as new kinds of agriculture emerge to support this trend. While both varieties offer unique characteristics and organic doesn’t always mean better, the choice between organic and non-organic Matcha ultimately depends on personal preference and priorities regarding farming practices and taste preferences since both adhere to strict regulations nevertheless and are safe for use.

Shop AVANTCHA Organic Ceremonial Grade Matcha Fuji

Shop AVANTCHA Ceremonial Grade Matcha Yame

Shop AVANTCHA Ceremonial Grade Uji Saemidori Hand Plucked

Matcha Evaluation and Grading

Matcha evaluation and grading present a nuanced process without a standardised system, even within Japan. Quality markers encompass various aspects such as foam, colour, aroma, texture, and flavour. While there is no official grading system, Japanese tea competitions offer insights into quality, albeit with limited availability outside Japan. Tea ceremony schools prioritise flavour profiles over grading, with koicha (濃茶) indicating sweeter, higher-quality Matcha suitable for ceremonies, distinguished by the character “mukashi” (昔) on the tins.

Usucha (薄茶) Matcha, characterised by the character “shiro” (白), is suitable for everyday consumption, as well as ceremonial. Additionally, Matcha grades like culinary, premium, and ceremonial exist, each with distinct characteristics. Culinary-grade Matcha, with its larger particle size and stronger flavour, is ideal for cooking. Cocktail or latte-grade Matcha offers a higher quality suitable for pairing with beverages. Ceremonial-grade Matcha, revered for traditional ceremonies, boasts vibrant green colour, fine texture, and a smooth, slightly bitter taste, ideal for standalone consumption.

Ultimately, choosing the right Matcha depends on its intended use, with culinary grades for cooking and ceremonial grades for drinking. To evaluate Matcha using the white paper smear method, spread a small amount of Matcha powder onto a piece of white paper to observe its colour and texture, aiming for vibrant green hues and a smooth, fine powder consistency.

How To Choose Matcha

When choosing Matcha, it’s all about personal preference and intended use. For the finest quality, opt for “Ceremonial” Grade Matcha, renowned for its premium taste and texture. AVANTCHA offers both Organic Ceremonial Grade from Fuji, Ceremonial Grade from Yame, and Ceremonial Grade Uji Saemidori Hand Plucked, all with distinct flavour profiles influenced by farming methods and terroir. Experimentation is key; adjust the thickness of your Matcha to your liking, whether you prefer the robust richness of koicha or the lighter touch of usucha. Just keep in mind that thicker Matcha contains more caffeine, so it’s best to avoid it before bedtime. For other endeavours, such as premium drinks, lattes or fine baking, a more accessible grade like our Ceremonial Grade Matcha Kagoshima is a perfect choice. Ultimately, enjoy Matcha in whichever way suits your taste preferences and lifestyle best.

Often, we have customers longing to enjoy the Matcha trend not knowing how to start liking Matcha. It can be an acquired taste if you’re new to Matcha, in which case we would suggest starting with delicious lattes and Matcha sweets and then slowly introducing other Matcha, such as a ceremonial grade made in the traditional style with water. We have listed the grades we offer below in the order you might like to try them.

Matcha Ceremonial Grade Natural Farming from Kagoshima

Tasting Notes: Leafy, Sweet, Umami

This is a beautiful, authentic Japanese Matcha from Kagoshima, Japan – a blend of the freshest, sweetest first harvest ceremonial grade tencha leaves, , giving it a naturally sweet, umami-rich flavour. These cultivars are nicely balanced to create a flavour that’s complex and with enough robust-character to shine through cold Matcha drinks, cocktails and lattes with superb clarity, making it a top-class ingredient for top-class beverages.

Ceremonial Matcha from Yame

Tasting Notes: Nutty, Smooth, Velvety

This single-origin Matcha from Yame, Fukuoka, boasts a nutty and velvety profile with hints of white chocolate and Brazil nuts, showcasing how smooth and sweet Matcha can be. Grown in fertile soils nourished by the Hoshino River and nestled among bamboo and pine forests, this Matcha reflects the incredible natural terroir of its origin. Enjoy as part of a traditional Matcha ceremony, made with water, or upgrade your latte to a more premium affair.

Organic Ceremonial Matcha from Fuji

Tasting Notes: Mineral, Robust, Verdant

Our Organic Matcha Ceremonial Grade Fuji is an excellent choice for connoisseurs who appreciate more complex, savoury, vegetal notes. Cultivated at the base of Mount Fuji in the mineral-rich volcanic soil of Japan’s Shizuoka region, only the top tencha tea leaves are plucked during the first flush of spring ensuring that rich, captivating green Matcha flavour with plenty of umami.

Matcha Ceremonial Grade Uji Saemidori Hand Plucked

Tasting Notes: Floral, Silky, Vegetal

A profoundly special and hard-to-find handplucked AVANTCHA Platinum Ceremonial Grade Matcha from Uji that we sourced this year upon our extensive travels in Japan. You have to taste it to believe it and we fell in love at first sip, savouring the super-rich, creamy and sweet flavour balanced with a deep, vegetal umami and high notes of spring flowers. The colour is almost hard to believe in a mesmerising, vivid-green with a soft, foamy texture. This is a truly magical Matcha to be made in the traditional style with water.

How to Store Matcha

Proper storage is essential to maintain the freshness and quality of Matcha over time. To preserve its flavour and nutrients, it’s best to store Matcha in an airtight container away from light, heat, and moisture. Once your delivery arrives, store it in the freezer until you’re ready to open it. Once opened, store it in fridge to retain freshness longer, however, take care with temperature fluctuations and condensation – once taken out the fridge, let it rest for a little bit before opening the container.

Additionally, Matcha is sensitive to odours, so it’s advisable to keep it away from strong-smelling foods. For optimal freshness, consume Matcha within a few months of opening the package, as it tends to degrade over time.

Sourcing

Sourcing high-quality Matcha requires careful consideration of several key factors, beginning with the tea’s origin. Regions renowned for Matcha production, such as Uji in Kyoto and Nishio in Aichi, are known for yielding superior-quality Matcha due to their fertile soil, optimal climate, and adherence to traditional cultivation methods.

While countries like China, Vietnam, and Thailand also produce Matcha, the highest quality and most authentic Matcha is typically found in Japan. Look for certifications such as USDA organic or JAS (Japanese Agricultural Standard) to ensure stringent quality standards are met.

Consider the processing methods and freshness of the Matcha, as these aspects significantly influence its flavour and overall quality. For instance, Matcha that is ground from tencha just prior to shipment, packed in nitrogen-sealed packaging, stored in refrigerated conditions, and transferred to cold storage facilities ensures maximum freshness. Establishing a business relationship with Japanese tea farmers often requires patience and trust due to the traditional nature of the tea scene in Japan, which can be a very special endeavour due to the personal touch of building meaningful relationships.

Packaging and Quality Control

The packaging of Matcha tea powder spans a spectrum from traditional to contemporary designs. Traditional methods often employ tin cans while modern packaging solutions have emerged, such as resealable stand-up pouches that are vacuum sealed, prized for their convenience and visually appealing designs that narrate each brand’s unique story. Regardless of the packaging choice, the aim remains consistent: to safeguard the Matcha from detrimental elements like light, moisture, and air, which could compromise its quality over time. To further ensure freshness, some producers integrate nitrogen flushing into their packaging process. Detailed labels on the packaging provide essential information about the Matcha’s origin, grade, and expiration date, empowering consumers to make informed decisions. Rigorous quality checks, including monitoring the temperature and cleanliness of cold storage facilities, are conducted to uphold stringent standards for taste, colour, aroma, and texture, guaranteeing a consistently high-quality product for consumers to savour.

Another question that we often get asked is ‘…why is Matcha so expensive?’ and as you can see from above, the depth of labour and love involved in producing this incredible product is lengthy, though entirely worth it. A bit like writing this Ultimate Guide to Matcha.

Matcha and Caffeine

Matcha, revered for its unique flavour and vibrant green hue, also boasts an intriguing chemical composition that contributes to its stimulating properties. Unlike steeped tea, where leaves are discarded after infusion, Matcha entails consuming the entire powdered leaf, leading to a more concentrated intake of its constituents. Chief among these is caffeine, a natural stimulant renowned for its ability to enhance alertness and concentration. However, Matcha’s caffeine content varies depending on factors such as cultivation, processing, and preparation methods. On average, a single teaspoon of Matcha contains roughly 30-35 milligrams of caffeine, about half the amount found in a standard cup of coffee. Alongside caffeine, matcha is rich in L-theanine, an amino acid that induces a state of relaxed alertness, counterbalancing the jittery effects of caffeine. This unique combination of caffeine and L-theanine fosters a sustained energy boost without the typical crash associated with coffee consumption. Moreover, Matcha contains potent antioxidants, notably catechins, which offer a myriad of health benefits, ranging from immune support to promoting cardiovascular health. Thus, Matcha’s chemical composition not only fuels vitality but also provides a host of other wellness advantages, making it a cherished beverage for both body and mind.

Matcha Health Benefits

Rich in antioxidants, particularly catechins like epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), Matcha aids in combating oxidative stress and reducing inflammation in the body. These potent compounds have been linked to various health benefits, including improved heart health, enhanced metabolism, and strengthened immune function. Additionally, Matcha is a rich source of chlorophyll, which supports detoxification and promotes healthy digestion. Its unique blend of caffeine and L-theanine provides a sustained energy boost while promoting calmness and mental clarity. Moreover, Matcha contains vitamins and minerals such as vitamin C, vitamin A, potassium, and magnesium, further contributing to overall well-being. With its impressive array of health-promoting properties, Matcha stands as a versatile and nourishing beverage that supports vitality and longevity.

Matcha Pairing

Wagashi sweets (和菓子), delicate and intricately crafted Japanese confections, offer a harmonious balance of flavors and textures that complement the nuanced taste of Matcha. Traditionally enjoyed together during the Japanese tea ceremony, wagashi and Matcha create a sensory experience that is both elegant and delightful. The subtle sweetness of wagashi, often made from ingredients like sweet bean paste, rice flour, and agar, perfectly contrasts with the earthy, slightly bitter notes of Matcha, enhancing its natural richness. These sweets are designed to be enjoyed slowly, allowing the flavours to unfold with each bite, making them an ideal accompaniment to the ritual of Matcha preparation and consumption. However, as culinary traditions evolve, more contemporary food pairings with Matcha have emerged, reflecting modern tastes and preferences.

What other flavours pair well with Matcha? Depending on the Matcha you prefer to drink, there will be different profiles that will work in their own way when paired with other foods. Generally speaking, the grassy-green flavours of Matcha can be complemented by sweet and creamy foods like white chocolate or lemony custards, fresh and vibrant fruits like strawberries, or served with Asian cuisine. For a particularly complex Matcha, we tested pairing it with caviar, with great success. The salty nature of the caviar enhances tasting notes and the oiliness gives an incredible texture in the mouth.

Matcha Recipes

From Matcha-infused desserts like cakes, cookies, pastries, and ice cream to savoury dishes such as Matcha noodles, salads, and even cocktails, the versatility of Matcha in culinary applications knows no bounds. Whether sprinkled atop yoghurt bowls or blended into savoury dishes, Matcha brings a unique and vibrant touch. We have created some exciting recipes for you – check them out here – and the pursuit of a new Matcha recipe never ends. Check back regularly for new additions or be sure to sign up for our emails. You’ll get free shipping if it’s your first purchase, too. Follow us on Instagram for more instant inspiration.

Ultimate Guide to Matcha References

Brekell, P.O. (2018). The Book of Japanese Tea. Bilingual Edition. 淡交社.

Chun, I. (2019). Everything you need to know about matcha quality. Yunomi.life.

Chun, I. (2018). Secrets about matcha. Yunomi.life.

Chun, I. (2018). How matcha is made. Yunomi.life.

Gascoyne, K. (2014). Tea: History, Terroirs, Varieties. Firefly Books, Limited.

Heiss, M.L. and Heiss, R.J. (2007). The Story of Tea: A Cultural History and Drinking Guide. Berkeley, Calif.: Ten Speed Press.

Kishida, M. (2022) All About Shading in Japanese Tea Cultivation. Yunomi.life.

Kishida, M. (2023). Looking for a matcha whisk? Here are some tips. Yunomi.life.

Kishida, M. (2022). Bamboo and the Art of Chasen Making. Yunomi.life.

Kishida, M. (2021). Befriending Japanese Tea Cultivars. Yunomi.life.

Kishida, M. (2021). Discover Koicha, the thick matcha of formal Japanese tea ceremonies.

Kumakura, I. (2021). Japanese Tea Culture: The Heart and Form of Chanoyu. Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture.

Mariani, A. (2021). How to evaluate matcha green tea. The Tea Squirrel.

Matcha Kāru. Matcha Test – A Tasting – The correct tasting and evaluation of Matcha tea.

Ooika (覆い香). 5 Famous Matcha Regions in Japan (Terroir Guide).

Sōsen, T. (2019). The Story of Japanese Tea.

Sōsen, T. (2017). Matcha – The Production of Tencha. Kill Green.

Tezumi. What is Chanoyu? | An Introduction to the Japanese Tea Ceremony.

Utermohlen Lovelace MD, V. (2020). Tea: A Nerd’s Eye View. VU Books.

Yunomi. (2019). Quick Guide to Japanese Tea. Matcha Latte Media.

Van Driem, G. (2020). The Tale of Tea. Leiden | Boston Brill.

Weugue, F. The Japanese tea cultivars. Japanese Tea Sommelier.

Wild, K. (2022). A Short Guide to Japanese Tea Cultivars. Kyoto Obubu Tea Farms.

静岡県茶業会議所. (2019). 茶の品種. 2nd ed. Shizuoka Prefecture Tea Industry.